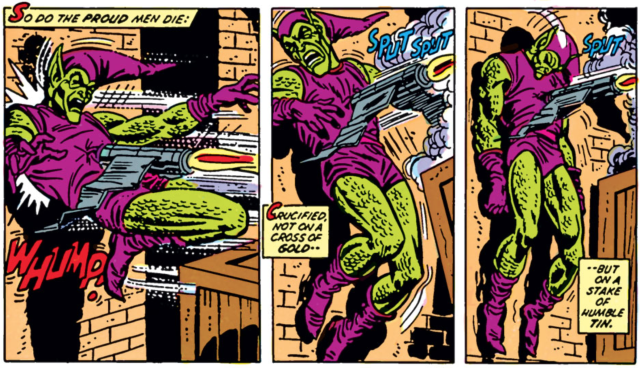

Unquestionably Norman Osborn had one of the best death scenes in all Spider-History.

It was a sad, tragic and emotionally impactful moment of comeuppance.

And that nasty old ‘Clone Saga’ just had to come along and ruin it, right?

I find this to be an over simplistic interpretation.

The scene still has plenty of emotional impact, perhaps as much or more than it originally had. It’s just that the specific impact has been altered from what it originally was.

One way or another there have been countless other examples of this phenomenon across Spider-History. For example in ASM #90 Spidey’s promised a dying Captain Stacy that he’d look after his daughter Gwen. The scene later became cruelly ironic in the wake of Gwen’s death.

In Norman’s case his death changed from the final note on Norman’s story to the final note on that era of his story.*

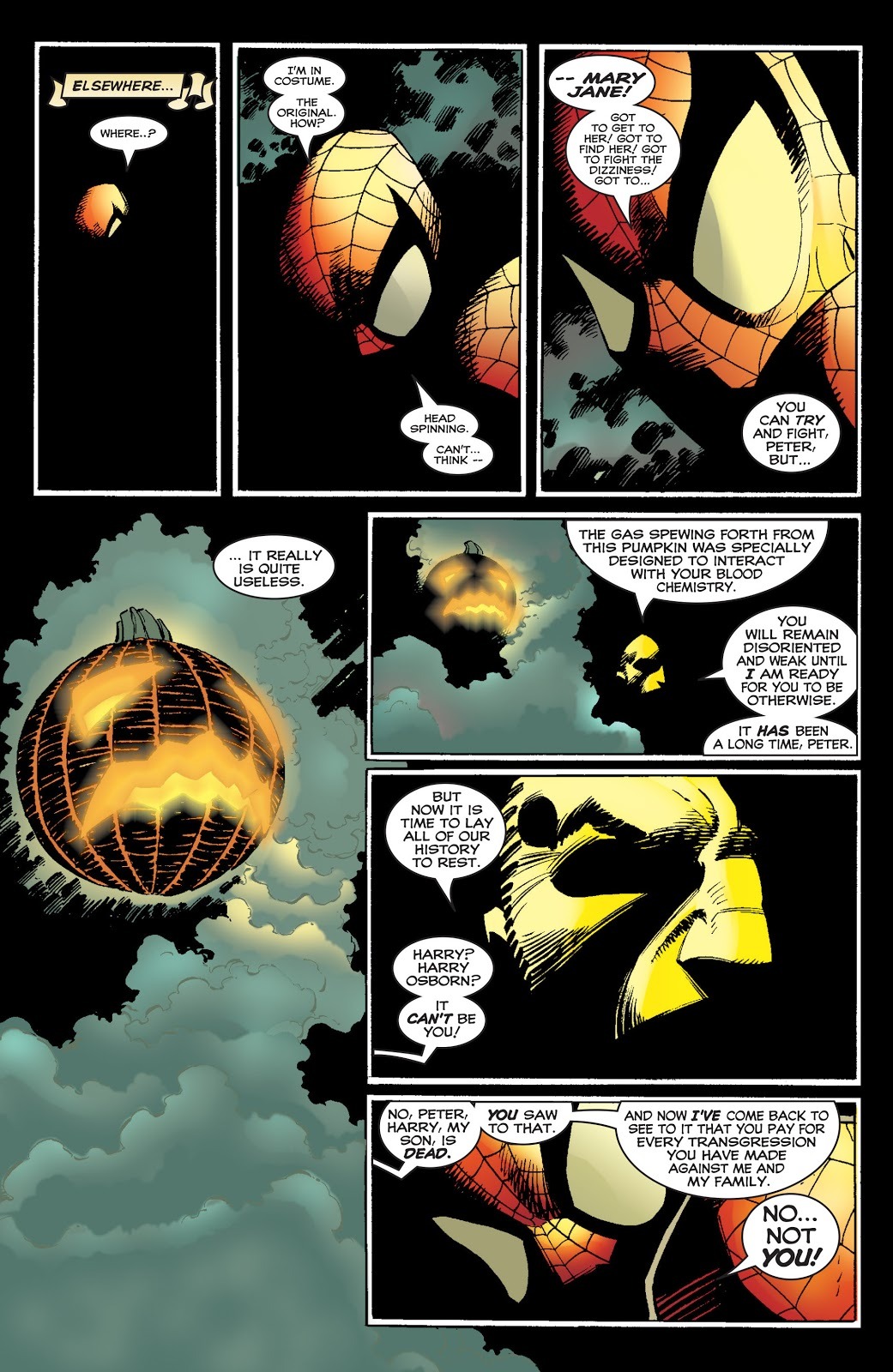

Rather than being the ultimate conclusion to Norman’s life it became the essential foundation for his sinister return. It was through his ‘death’ Norman was able to amass greater power and resources that transformed him into a more potent adversary thereafter.

I liken it to Lord Voldemort from Harry Potter.

Voldemort faced a seemingly absolute defeat when confronting Harry as a baby. But this defeat set the stage for his horrific restoration mid-way through the initial seven novels.

To paraphrase ‘Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban’, Norman, like Voldemort, arose again ‘greater and more terrible than ever…’

His ‘death’ remains tragic, but no longer because it represents the ending of a life.

Now it is because we know how it shall lead to further pain in the life of our hero.

*Similarly the over all storyline in ASM #121-122 transitioned Peter and the Spider-title as a whole into a new era. You could even look at it as the prelude to the 1990s ‘Clone Saga’.

This is appropriate since the story already retroactively set up the 1970s ‘Clone Saga’, the ‘Hobgoblin Saga’ in the 1980s, the ‘Harry Osborn Saga’ in the 1990s and other tales too.

So there was already a precedent for Norman’s death being a ‘beginning’ rather than an ‘ending’ anyway.

P.S. I suppose you could argue Norman’s return ruined the comeuppance he faced for Gwen’s death.

But honestly by 1996 this was rather appropriate. Villains like the Joker had committed no end of horrific crimes for which they’d merely been temporarily wounded and then equally temporarily imprisoned.

Such situations emphasize the inequity in life, namely how often the good die and the evil live. In doing so it provides a greater need for heroes like Spider-Man to try and avoid more Gwen Stacys falling prey to the Norman Osborns or Jokers of the world.

Plus, circa 1996, Norman’s son Harry had destroyed himself and Gwen’s death had been an important contributing factor to that.

In response to Bruce my bad. The return of Norman doesn’t diminish his original death. His first death is still pretty powerful and tragic in the fact he came back to torment Peter more. Worse he showed no remorse for the death of Harry at the time makings him more of a monster.

In response to Tayo… I never mentioned the death of Gwen. I mentioned issue 122, the death of Norman, only.

In response to Bruce, the resurrection of Norman does not ruin the impact of the death of Gwen. She is still dead while the mobster responsible for her death is still alive . Yeah I am still kinda annoyed that they brought back Osborn, even if he did star in some good stories afterwards, but sadly death was not irrelevant by the time Osborn came back. It is not like he is the first badguy to come back to life

Norman “coming back” definitely ruined his death scene. If he’s not dead, that was not a death scene in ASM # 122.

Sadly, I get the feeling that the only way Marvel could “get out of” the terrible, terrible Clone Saga, was to bring Norman back to life (as the driving force behind the Clone Saga). I believe Marvel never saw the overwhelming backlash to the Clone Saga as a possibility. They thought the Marvel fans would love it (having 20+ years of Spider-Man stories actually NOT featuring Peter Parker, but the clone). When it exploded in Marvel’s face, they had to do SOMETHING to get fans to settle down.

One last thing. If Norman’s Goblin Serum allowed his pierced heart to regenerate/heal, then why would he still have simple skin scars on his chest (from the glider impaling him)? Things that make you go, “hmmmm…”.

@Alex: I figure certain bad guys attract customer interest and sales, so they can’t ever get executed or die in prison, etc. It’s also easier to stick with one stock character, then keep duping old ones with new characters who just have the same power-sets. Like, how many electricity-themed villains does Spider-Man need? Just keep the one Max Dillon (or now Francine Frye) around. It’s simpler. (I’m indulging my imagination-amusement of a Batman story where the Joker goes on the run in the Texas hill country, and gets shot dead by a group of Texas Brownies out on a hike. I used to live there, and they could do it).

Or it’s just as possible that readers may have wanted a Goblin but weren’t actually demanding Norman be brought back before the Hobgoblin first appeared?

Po-tay-to, po-tah-to.

@hornacek, then I guess Stern was misremembering or being misleading in his Crawlspace interview

I’ve read Stern interviews over the years and while he says that Marvel wanted him to bring back “a Goblin” I never heard anything saying that (a) Marvel wanted him to bring back Norman, or (b) the readers wanted him to bring back Norman. As someone who always read the letters’ page in every ASM issue, I don’t remember ever reading letters from readers during the pre-Sten era (Wein/Wolfman/Oneill) saying “You should bring back Norman”. Like Marvel, the readers may have wanted “a Goblin” but as far as they were concerned, Norman was dead and it was ancient history.

@Jack Brooks

There are two ways of looking at that, one more cynical than the other.

The cynical point of view is that because the characters never end the heroes never get what they want and the villains never truly get their comeuppance, this then (arguably) reflects real life where the majority of the time most people are not satisfied with their lot. Even in the Silver Age when villains weren’t nearly as violent as they are perhaps now their crimes would realistically earn them jail times that would send them away for an extensive number of years.

And that’s not even considering their breakouts and repeat offences. At this point even a B-lister like Shocker (who is far from a serial killer like Carnage) will have racked up enough jail time that he’d essentially be imprisoned for the rest of his life were he to just live out his sentences. Even if he somehow earned time off for good behavior or parole (highly unlikely given his record and skillset) he wouldn’t be coming out of the slammer any time soon. This means the options for these characters is the Thunderbolts program or inevitably breaking out of prison.

Therefore practically EVERY super villain never ‘gets what’s coming to them’ within the context of the narrative. None of them ever stay in jail long enough for justice to have been served. Hell, even death isn’t permanent for most of them.

The less cynical, perhaps even optimistic, interpretation is this. The villains by virtue of their very natures and existences are continuously ‘getting what’s coming to them’ because they are doomed to live hollow, unhappy, unfulfilled lives on the fringes of society.

They can never know the joys of a family life. They are always going to be looking over their shoulder. Most of them can never have true financial security and even if they did (like Lex Luthor or Norman Osborn) in the deepest recesses of their soul they are never going to be truly happy. They might get a thrill out of dueling their mortal enemies but deep down, they are broken.

Stories like the Killing Joke and Maximum Carnage even reveal how ultimately wretched and pathetic psychopaths like Joker and Carnage are. Their murderous mayhem is merely a distraction so they need not look back at their pasts nor in the mirror. The heroes by contrast ultimately live richer and more fulfilling lives in spite of their scars and hardships. This is illustrated neatly in Jenkins’ ‘A Death in the Family’ where Peter walks away from everything Norman has done to him, hurt but ultimately whole, and the worst thing he can do is let Norman live as his miserable old self.

“I also think that when murderer characters never get punished, it plants a bad message in the impressionable.”

We should never ever cater to those who are foolish and/or impressionable. That way leads to madness. By this logic we shouldn’t have seen Kraven the Hunter commit suicide, even though that was him getting his comeuppance. And again, literally every super criminals never ‘gets what’s coming to them’.

“I realize there are some bad guys who are so iconic you can’t really ever get rid of them. But some of them are so bad, they really should pay the ultimate price. (Like, I’m on Jason Todd’s side of this argument, regarding the Joker).”

For the Joker though, having Batman or one of his protégé’s kill him would be the absolute ultimate victory. This is thematically illustrated through the Batman Who Laughs character, the Injustice timeline and Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker. Even though the Joker doesn’t want to die per se making a hero cross that line would be giving him the last laugh.

Additionally if the rule is iconic characters can’t be killed off then it applies to the Joker above every other character as he is without question THE most iconic super villain of all time.

@hornacek

Roger Stern has talked about that multiple times. IIRC he might’ve discussed it in either the Origin of the Hobgoblin or Hobgoblin Lives trades from the late 2000s/early 2010s.

However, I’m 99% certain he discussed it on his interview with Crawlspace way back in the early days of the podcast circa BND.

Fans kept asking but he didn’t want to restore Norman so he created Hobgoblin.

“And the Hobgoblin’s creation was directly in response to fans asking for Norman to return”

Wait, what? I have never heard this before. Every interview of Stern I’ve read about the Hobgoblin said that Marvel wanted “a” Goblin but it was never specified to be Norman. Stern didn’t want to reuse Harry, and he didn’t consider Norman and Hamilton options because they were dead. He said he wanted to create a new foe, someone as cunning as Norman but without the insanity, therefore more dangerous, and whose identity would be a mystery.

As someone who started reading ASM during the Wolfman run, and starting to actually collect the title in the Stern run, I never heard during that time (or since) that readers were asking for Norman to return. By the time Hobgoblin appeared Norman had been dead for 10 years. Most of the current readers at the time either accepted Norman being dead as part of the status quo, or (like myself) only knew Norman as someone from Spidey’s history who was already dead when they started reading the book.

I definitely don’t think it’s a good thing generally that villains almost always come back, especially if they had no dramatic potential past their deaths (like in Kraven’s case, before Hunted fixed things up), but in Norman’s case, I feel like we got the best possible result from the convention, especially since he had tons of potential left.

Personally, I would prefer it that super-villains get what’s coming to them, eventually. For example, “Hunted” cleared the deck of dozens of B- and C-list bad guys, and I was okay with that. I also think that when murderer characters never get punished, it plants a bad message in the impressionable. I realize there are some bad guys who are so iconic you can’t really ever get rid of them. But some of them are so bad, they really should pay the ultimate price. (Like, I’m on Jason Todd’s side of this argument, regarding the Joker).

@William Sinclair

Hopefully times will change and that need not be an inevitability. Major villains should be capable of being written out if appropriate. It’s all about the big picture and the what the over all franchise needs. In 1973 removing Norman was the right move for his character and the over all Spider-Mythos. However, things had played out in such a way that by 1996 it became right to bring him back.

To add to your point though, let’s remember Bill Mantlo intended to bring Norman back in the 1970s as Carrion IIRC. And the Hobgoblin’s creation was directly in response to fans asking for Norman to return and Roger Stern not wanting to do it. IIRC weren’t there some fans speculating that the mysterious person possessing the alien costume might be Norman Osborn, before we learned it was in fact Eddie Brock.

As I said above, his return never ruined the impact of his death. It merely altered it from one meaning to something else. This is owed to Norman’s incredibly impactful return which is one of the darkest and most emotionally wrenching Spider-Man stories ever.

Let us also consider that Norman’s death is what enabled him to build up a new power base for himself which enabled him to attack Peter in ways he’d never been before.

The way I see it, major villains in ongoing superhero comics are always going to come back eventually, no matter how memorable their death scene, the fact that Osborn got to stay ‘dead’ for so long after his is impressive in and of itself. If he’d come back a few issues later, I’d probably agree with the consensus that it ruined the impact, but the massive gap between his proper appearances helped make it seem as though the initial ‘death’ still mattered, and gave his return a suitably grandiose feel.