By the end of each arc from J.Michael Straczynski and John Romita Jr. (with inks provided by Scott Hanna and colors by Dan Kemp), a sense of consistency prevails in The Amazing Spider-Man comic book; a title focused on the development of Peter Parker – now more mature than he’s ever been in his entire life and self-conscious of the totemic power he emboldens. His adulthood characterization has reached new depths, as every (real) person undergoing the same phase would – which makes an intriguing exercise for readers to observe how the priorities in his life have changed. But that’s not incidental.

During the Ditko & Lee years, Peter Parker grows from the maladjusted teenager in high school eager for acceptance to the pre-adult who joins the university and becomes a more grounded man. The overload of personal sacrifices increases proportionally to the life risk danger of his superhero battles. He’s forced to grow up in his mind and spirit. His is such a demanding life overburdening with guilt that he could no longer act naturally in his own age. That’s Ditko’s legacy and fiercest contribution to the character: the bad side of being a superhero. When John Romita replaced him, Stan Lee took full reign of the script duties, often letting Romita take part in the plotting (the Marvel Method). The title acquired a Norman Rockwell redesign and Peter Parker gained his defining and recognizable look (second only to Clark Kent). He started to develop healthy relationships with his colleagues, and even women; his jokes and pranks with villains and J. Jonah Jameson evolved, thus granting the title a lighter tone.

The works of Ditko/Lee/Romita compose the template of what an Amazing Spider-Man comic should be, later established by Gerry Conway with Gil Kane and Ross Andru. And for a while, it was good. Then came the nineties. The trend at the time was to convey dark and brooding self-reflection in superheroes through a simple formula: the older superheroes became, the deeper they delved into the abyss of their own twisted consciousness. It was maturity moving backward: full-grown superheroes, instead of conforming with their adulthood and acting with more reason, would emotionally devolve and act like impetuous children, unsure of themselves and their actions. Contradiction. Kids wanted their newfound adult superheroes to react as unrelenting adults and still formulate thoughts like their readers. Whereas the villains, were regarded just cannon fodder to move the story forward, like Judas Traveller, Gaunt, and the Brotherhood of The Scriers, for instance; they were given more screen time (pages) than necessary, building secrets within secrets, based on retro continuity stories, to make Peter Parker’s life more complicated than it already was. As a result, that put the main character in a constant state of alert as if he was always Spider-Man even without the mask, like Batman. So the relatability factor from the original concept – “the super-hero that could be you!” – was long gone.

It was a dark period for comic book storytelling and the Spider-Man editorial group had no other choice at the time but to dance according to the music – a theme already covered in this column – and spread the formula across all through Spider-Man titles published at the time: endless unresolvable plots featuring most of Peter’s friends and acquaintances’ developing ties with old and new arch-enemies. An entire supporting cast redesigned to either endanger his life (occasionally Aunt May and MJ’s) just to push his sense of guilt and responsibility to the extreme or to present dark pasts that would later interfere require Spider-Man’s direct intervention. Peter Parker’s core characteristics had faded in his own comic.

Another factor worth noticing that exemplifies the aforementioned problems can be surmised in Peter Parker Spider-Man #14 vol.2 (Feb. 2000)

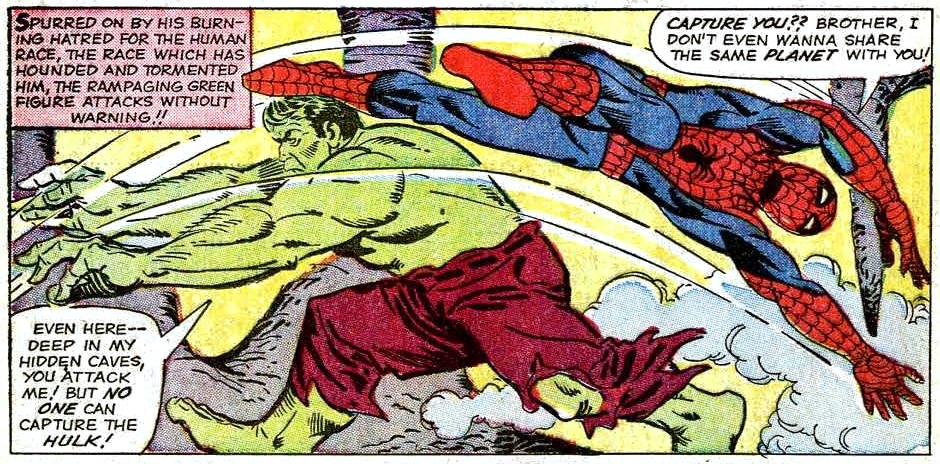

This issue alone represents the chaotic storyline structure from the time: Mary Jane had been considered dead; instead of a proper portrayal of Peter Parker in a deep state of sadness and denial (as the title of the story suggests), the entirety of the issue is a visual fight between the hero and the Hulk. Although it is quite comprehensible that a Spider-Man issue should (in theory) contain scenes depicting the hero executing extraordinary feats of his strength and abilities against an antagonist, the mere insertion of physical combat without any previous explanation as to how and why such fight came to be wouldn’t make the story more interesting and digestible to the reader – without at least a proper reason or a built-up from presented in the previous issue. Still, the story begins with every single supporting cast member of the title (twelve in total) grieving over her alleged passing. Whereas Peter’s bare face is only shown in the issue’s last page. Let’s not forget: this comic book title is Peter Parker. If the whole premise of the title seems contradictory to the story itself, it’s because it is.

The new century dawns and Marvel Comics reconfigures its own editorial management. Axel Alonso drafts J. Michael Straczynski to the ASM title, who applies his approach to the hero: character is the force that moves the story forward. Strategically, Joe Quesada makes an official statement that in the Marvel chronology, ten years have already passed since Reed Richards, Susan Storm, Ben Grimm, and Johnny Storm landed back on the planet, totally transformed and changing the planet they live in as a consequence. The rest is ongoing Marvel history. In ten years, after so many challenges, defeats, strange tales, silent victories, and journeys into the mystery, it is safe to state that Peter Parker has had his share of experience and growth. He’s been above and beyond earth; traveled to other dimensions; fought alongside gods and helped defeated their nemesis; he can keep up a scientific conversation with some geniuses of his era. From a psychological perspective, Peter Parker’s learning curve grants him more intelligence and experience than most of his peers. Even artist Todd McFarlane adds that fact in his first venture as a writer in “Torment” – first published in Spider-Man #1 (Aug. 1990):

In hindsight, with all this baggage in his record, Spider-Man can and should be always regarded as a first-tier superhero – which in fact he is to his readers and popular culture in general -, but keeps being pushed back to a mental/emotional status as a young rookie. The very template that defines the uniqueness of Spider-Man is still the rule that most of his writers (and editors) rely on to tell the refurbished tales that quench the thirst of nostalgia – a cultural phenomenon permeating many layers in all forms of the entertainment industry; comic books are no exception.

Under Straczynski’s keyboard, there is just the acknowledgment that his interpretation (not version) of Peter Parker upholds his history, gets older, and moves forward as a man. Up to this point on their run, JMS & co. reexamined many aspects of Peter’s psyche based on his origin and tested his limits at different arenas, proving that Spider-Man is one of the most flexible heroes in the superhero comic book realm. He adapts, learns, overcomes the challenges, and evolves. He’s the hero, the spider, the scientist, the nephew, the husband, the teacher.

Last but not least, the friendly neighborhood Spider-Man.

THE DIGGER – ASM#51-54 (vol.2):

(Covers by J. Scott Campbell, John Romita Jr., and Terry & Rachel Dodson)

In the Marvel Comics continuity, science and technology are allowed to be extrapolated, as much as it can be imagined. It’s a fictional realm, a Universe that is in constant expansion, which creates endless possibilities. For the first time in Spider-Man’s publication history, Spider-Man’s origin has been reimagined – not only with a cultural/totemic possibility but resignified from a scientific perspective. It’s one of the factors that make the JMS & JRJr run in the title so remarkable. Another is the absence of old foes (save for Doctor Octopus) whose motivations of vengeance and perpetration of evil are not linked to a supporting character. Instead, it features new antagonists who are directly proportional to Peter’s reexamination of his persona without the dark brooding posture that would lead to an emotional downward spiral; so they serve a purpose to the character. His life as the masked hero is the sole element that moves the story forward. Straczynski knows what that means: he puts his characters to the test and rips their core wide open, letting the reader be the ultimate witness (and even jury) of their actions.

In this arc, the first test comes in the form of a Hulk – of sorts.

By following Spider-Man’s classic rogues’ gallery tradition, JMS & JRJr. introduce The Digger in the same mold – but with a more sinister twist: thirteen Mafia mobsters from the late fifties who were executed had their bodies dumped in a large hole in the Nevada desert, once used as an illegal dump for chemical factories.

By following Spider-Man’s classic rogues’ gallery tradition, JMS & JRJr. introduce The Digger in the same mold – but with a more sinister twist: thirteen Mafia mobsters from the late fifties who were executed had their bodies dumped in a large hole in the Nevada desert, once used as an illegal dump for chemical factories.

Many years later, a Gamma bomb is tested nearby. The outcome is a mix of body parts unnaturally glued into one single body; it’s the Frankenstein concept extrapolated within the scientific possibilities of the Marvel Universe. But he’s seeking righteous payback, even justice in his own distorted vision, for what has happened to what happened to all the men who form him. That’s an origin told within five pages with great text, artwork, and color.

NOTE: In order to enhance the fictional believability, JMS employs his journalistic skills to tell this tale as if it were an excerpt from a genuine book (A Brief History of The Gangland Wars, 1950-1963 – by Marshall LeGrand), followed by another one from a military scientific report, also written with accuracy. Fictional historical writing within a Spider-Man Comic Book.

Back to the story, Peter is now collecting the compensations from the internal (and external) journeys he’s been through – May knows his secret identity. He survived near-death battles against “natural enemies” that led to revealing of the true Spider nature concealed in the man and the rebuild of the man around the Spider. Mary Jane has returned to his life. It’s a new beginning, with respect for chronology and all the proper storytelling elements in place.

The Digger reaches New York and makes his objective is clear: find the mandant of the execution who sealed the fate of the Mafia bosses decades ago: Morris Forelli. This bizarre amalgamation of lost souls starts with the delivery of a message by simpling bringing down a building. William Lamont investigates the crime scene and finds a clue that might require a certain friendly neighborhood’s assistance. Though such a professional relationship might be inspired by James Gordon and Batman’s, theirs builds up to be more acid, embedded with rapid-fire quip-pro-quips. Still, Lamont is a character who embodies a father figure to Peter and even an unmentioned resemblance to Ben Parker. And since they’re working towards the same goal, it is a relief to see Spider-Man earning once more the respect and back-up from an officer of the law.

One piece of dialogue worth noticing (below), is Lamont’s speech on how the superpowered costumes battles interfere with people’s lives; if there was ever a first teaser of the Civil War event in the pages of ASM, this was it – three years before its release. A seed subtly planted into the Marvel reader’s mind, harbingering things to come.

Up until now, Peter has been subjected to trials that delved into his arachnid nature, psyche, intelligence, feelings, and psyche; in this arc, his moral code is put to test.

When the Digger attacks again and Spider-Man finds him by following the sirens, he loses the first battle. But from this single confrontation, besides finding leads that corroborate Lamont’s assumption on who the Digger is, he’s summoned by Peter Forelli, who’s ahead of the curve and hires Spider-Man’s services to protect him and his daughter. Forelli’s convincing argument weighs not only by asking Spider-Man to quickly intervene whenever the Digger might strike but also by paying him ten thousand dollars a day – money he could put into good use, especially now when MJ is back in his life; his teacher’s salary is not enough to provide for things he would like to do with and for her. After all, he would be doing nothing but his job: protecting people and fighting menaces. It’s a situation worth observing because the scenario has drastically changed regarding Peter’s financial status: no longer he needs to expose himself as a menace through pictures published for the Daily Bugle and feel ambiguous about his own actions the next day because he needed money; he makes a living out of his job as a teacher and is fulfilled about it. But now MJ is back in his life. Any loyal husband wants to provide the best for his wife, and here’s an opportunity to do so. It is neither a sinful/selfish temptation, nor the start of a new phase as a hero for hire, but a chance for Peter to be financially rewarded for being Spider-Man as a hero, and not as a variety entertainment act when he first donned the spider-uniform before Ben Parker’s death – a teenager barely emulating adulthood. It is a form of acknowledging Peter’s growth into a man with an emotional purpose. He loves MJ with all his heart and wants to do right by her.

Distinct aspects of Peter’s development as a character through his intellect are depicted in this arc – and not in a cartoonish way.

First, as a responsible teacher, because being a scientific genius is not enough; how to transmit and apply the information (as he did in the first arc of JMS’s run) makes the whole difference. In this story arc, he stands before his students and tells them how science should be perceived and applied; a monologue that, besides enforced by JRJr.’s art to illustrate The Digger’s adaptation to a new century, deserves high praise to this day for its thought-provoking erudition.

“Knowledge is what makes the difference between the world you want, and the world other people think you should have. The three key ingredients in science are observation, analysis, and replication. You observe what’s happening, analyze the possible causes, then attempt to replicate the events to verify that your analysis was correct. But it all starts with observation. It starts with making a conscious effort to be aware of the world around you. Because this isn’t just about science. It’s about developing a mind that examines what you see and hear, from the media, from politicians, heck, even from your teachers — with the understanding that of course this teacher is always right — so you can critically determine the truth of what you see, hear and believe. Otherwise, you will find that truth is a constantly shifting concept. Observation makes you aware of life. So much of the time, we let the moments pass by without really seeing them, appreciating them. We get so caught up in where we’re going that we don’t see where we are. A scientist has to think about the future but lives in the moment, see the moment. Otherwise, the world can just pass you by.”

After this excerpt, the second is self-explanatory: without being the same freelance photographer selling pictures for the Daily Bugle – hence JJJ’s absence -, his analytical mind is free without guilt or concern with third-tier supporting cast members. He gathers data from Lamont and Forelli about the Digger and goes investigating his provenience in Nevada. Due to chemicals’ artificial preservation of the bodies, they didn’t decompose – the gamma burst merged them into a cohesive body that cannot be killed. A great scientifical discovery (within the scientific, mystical, and supernatural laws of the Marvel Universe), but bad news for Spider-Man. Still, know your enemy.

This is how the creation of a single villain can exert proper function in a superhero, especially when told with proper elements, dialogue, characterization, and technique. The board is set and the pieces start to move. It’s a master lesson in cinematic storytelling applied to comic book format.

NOTE: It’s no wonder that Dan Slott (when took over the ASM title as the sole writer after the Big Time storyline) reimplemented the scientist’s side of Peter and took to the extreme; an idea first introduced by JMS.

Third, Peter Parker’s sex life.

Art – even in its mass-produced form -, will always reflect portions of the collective thinking, cultural values, and behavior from the same people responsible for making it. Sometimes, authors and artists from distinct continents can influence one another by their works. And history will tell how a work of art had the elements that still endures the test of time. It’s happened in the cinema, music – and comic books. Consider the perspective. The British invasion in comics in the USA spearheaded by Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Jamie Delano, Grant Morrison, Warren Ellis, Garth Ennis, and others have left their mark in the history of superhero comics forever because they were once enraptured and influenced by the genre itself and switched the angle in how it could be looked at. It is not the subversion of the genre but a change in its perspective. Here’s another one: french (comic book) writer/screenwriter/director Alexandro Jodorowski once stated during an interview that he abhors the North-American superhero culture; mainly pointing out that these characters are devoid of earnest human feelings and urges – due to their lack of penises. It’s worth noting that, the sex portrayal between the European and North-American entertainment cultures is abyssal because of the way each culture approaches sex. Does that mean the superhero comic book industry should depict – if not imply – more sexual activity from their characters just because in reality, that’s what human beings do? And if Spider-Man is the most human superhero of all, shouldn’t he be given more stories with sexual content? Probably dealing with impotency as Nite-Owl did in Watchmen? Or since he also fights against street crime, shouldn’t he be chasing human and sex traffickers, rapists, assassins, and drug-lords? Probably not, because having ‘real-life problems’ does not mean the character should fight social problems on a real-life scale.

His personal life as a masked hero is the very theme of his stories – how a common kid bestowed with amazing powers react to the responsibility of his actions being forced to grow up in his mind and heart, and never give up in his battles, either personal or physical against enemies who endanger the society he’s part of – because he is the average guy like anyone. His moral code is also one of his superpowers – something that is not cynical. That is his appeal to the masses (children included).

So it makes sense that the hero in his comic book continuity, cannot have harsh stories told at the same level as John Constantine or even Batman in the recent post-Vertigo Black Label imprint. That doesn’t mean that such themes are not strictly forbidden to be approached; subtlety is the strategy. Stories such as The Death of Jean DeWolff, Kraven’s Last Hunt, The Death of Gwen Stacy, and The Evil That Men Do still deal with serial murder, suicide, drug use, and rape, respectively, without the raw visual depiction of such themes.

Subtlety is also applied by Straczynski in this arc when the subject is sex in a Spider-Man comic book. In fact, it is right there, in issue #51 (#492 – vol.1) when, before his first strike in the building used as a one night stand place for sex workers, a man in a car is talking to a prostitute asking how much her services would cost; nothing unusual, but for a Spider-Man comic book, it shows a slice reality that cannot pass unnoticed: the theme is sex.

When Peter and MJ celebrate their reunion as a married couple, she teases him with an old sexual game they used to do it; it is not mentioned but clearly implied. Moments later on the same issue, she is shown with her back bare to Peter while changing clothes – He can barely contain his fascination. (Nothing new here, because the same scene has been illustrated many times over through different scenes ever since they got married. Scenes that showed that Peter and MJ would definitely do “it”, only to have them cut and have the stories either transposed to another situation or ended.) While flying to Nevada on a Forelli’s private jet – in costume – in order to investigate more about The Digger, he’s offered the services of a woman paid to do to him whatever he wishes, but refuses; it’s an insight on how Peter deals with his sexual urges.

Sometimes, (superhero) stories of good vs. evil are not enough. Surely they do teach us the levels of morality and define what is wrong or right by definition and how superheroes’ altruism can light the path to do what is right: but the path to self-discovery is something else entirely: it can involve Love, loss, mysticism, mystery, strange adventures and encounters, sacrifice, donation, humbleness. These things also relate to us because they’re part of our nature. The JMS run only reaffirms that Peter is a man of principles and integrity – also devoted to the woman he loves. This phase establishes his adulthood with great respect for the character’s history and also for the adult fans who have grown up with him and have been along for this superhero soap opera ride for the last decades; who are quite well-aware of how his life has been until now. This is a superhero comic book that respects the continuity of the character and rewards the reader from Peter’s perspective and authentic human relatability to the point he thank God once more for being back with MJ. Getting back to the Love of our life can be one of the most important moments in our existence. And the scene (below) portrays an earnest human emotion: gratitude.

Peter and MJ are visually portrayed after having sex in bed. It is subtle and sincere. Another proof that a well-structured superhero can not only display unconceivable action, characterize malevolence followed by violence, but also convey a peaceful emotional response. From there, the appreciation turns into inspiration. Therein lies the consistency and subtlety of Straczynski’s approach to their characters: by going straight into the core of their minds and hearts.

By the same token, not even the supporting cast for this arc is spared from the same technique: there’s a conflict between Forelli and his daughter, Lynne; he knows that he must atone for his actions made in the past – including the Digger’s creation. He’s sorry for it all because she believes her father has always been a good man and would do anything to protect her; when she sees him paying Spider-Man for his services, it only reinforces her resolve on the wall-crawler. Spider-Man’s consciousness and attitudes turn into a predicament that makes even the reader question the hero’s moral standards. A plot device that coincides with a quote from Straczynski’s on the matter:

“Understanding is a three-edged sword: your side, their side, and the truth.”

It’s relevant to reiterate how JMS approaches his villains as well, and the Digger is not an exception. One of his greatest skills as a comic book writer is how he distills all of their psychological, emotional (and even physical) layers – without the romanticization of malevolence in order to understand the villain’s nature and motivation, thus making the reader draw the line to define who is who and what roles they play according to the situation they’re thrown into in this fictional realm; his creator-owned mini-series Sidekick explores exactly that.

As the arc approaches its climax, all the pieces are in place for the final movement.

After engaging the Digger in battle twice and losing both of them, Peter does his homework – investigative work with the gathering of information, detection, logic, and scientific deduction. He learns that the Digger’s molecular structure defies the laws of nature by being alive – the Gamma radiation is the element holding together different body parts altogether into one. However, the tension to keep this structure cannot last long. Know your enemy.

Let it not be forgotten: Straczynski’s and Romita Jr.’s Spider-Man is a superhero at the peak of his rational, emotional and intellectual prowess; a scientist with acute and analytical perception. But he is now a man in control of his psyche as well – making his mind part of his exceptional abilities. In order not to lose again, he ‘ignites’ the Spider and lets its predatory nature take control of the fight and go for the kill in a no-holds-barred brawl. And since he’s quite aware this walking-talking half-dead jigsaw puzzle is not even a person, just like he did with Shatra and Morlun.

It is scientifically proven (in the Marvel Universe) that the Digger’s has never been alive. Besides, there’s no moral code to be rationalized, no room for hesitation – notably when fighting a Hulk.

This arc presents a forensic approach to character storytelling: there are underlying themes which, if dug out (pun intended), can prove once again that, no matter what happens, the core will always be the life of Peter Parker as Spider-Man. If he’s to fight a Hulk, the whys and hows are acknowledged. Amidst the action, there’s also space for drama, the examination of personality aspects, and surprising resolutions. Over an arc of four issues, much about the character of is distilled: his acceptance and use of the Spider-totem; Mary Jane’s comeback and his fidelity as a husband tested; how his mind acts and reacts in a fight; what he does with the money he’s paid for being a hero for hire – an act which pays huge respect to the memory of Gwen Stacy – by building a memorial library under her name in the school he works at. He even figures out how to defeat the Hulk – permanently.

All in all, there’s not much impact on the hero’s chronology, but the arc respects it – also functioning as a statement of how far he has evolved and how challenging his stories can be.

J.Michael Straczynski is not only leaving his mark on the title, but he’s also building a better Spider-Man.

Kudos to the art team as well: John Romita Jr.’s art keeps evolving with Scott Hanna, who adds depth and gravity to his pencils, whereas Dan Kemp’s colors provide a real luminescence into each page. It is well-produced and structured; a cinematographic lesson in super-hero comic book storytelling.

The page below determines that:

“The JMS run only reaffirms that Peter is a man of principles and integrity – also devoted to the woman he loves. This phase establishes his adulthood with great respect for the character’s history and also for the adult fans who have grown up with him and have been along for this superhero soap opera ride for the last decades; who are quite well-aware of how his life has been until now.”

This is very true but I feel compelled to chime in with the fact that it spoke to people like me on the opposite end of the spectrum. I began regularly reading Spider-Man when I was 9 (we’re talking post-Clone Saga stuff) and had recently turned 13 when the JMS run began being reprinted over here and over the course of several issues it not only won back my faith after Mackie’s run but also really spoke to me. I really LIKED seeing an adult Spider-Man at age 13. And I was reading USM at the same timetoo, had been for years. But I preferred JMS’ stuff.

You are too hard on some of the 90s comics because as with all eras there were gems to be found (ASM #400 for example).

I think you’re a little too hard on 90s comics. While I see where you’re coming from, the heightened stakes of those stories instilled a sense of foreboding and unpredictablity that was really exciting as a reader at the time. Of course some stories were very convoluted with a lot of plot-driven events being stretched beyond their breaking point. And some villains like Traveller were pretty bad and forgettable (but every era has its bad villains… I’ll still put the 90s up against the 70s when it comes to that). But to your main point just because you’re an adult doesn’t mean you have all the answers worked out…. Peter is presumably in his mid to late 20s and has multiple tragedies befall him in quick succession and of course that leaves an impact on his mental health and may influence his behavior in a negative way. Look at his friend Harry who went insane under the pressure of his paternal expectations and PTSD in the critically acclaimed JM DeMatteis Spec run. Adults can definitely act irrationally and some do regress to childlike impulses of anger, doubt, bitterness and insecurity during prolonged periods of extreme stress. This is not unique to the 90s, as JMS himself wrote ‘Back in Black’ a rightfully acclaimed story that reuses this version of a dark and somewhat broken Peter/ Spider-Man brooding, immersing himself into his hero alter-ego and out for revenge. As for the Spidey being treated like a rookie stuff…. I don’t think that came into play until the Slott era. Peter was actually very competent in the 90s and more like an old pro than he had ever been before and has been since. A lot of character progreession came to halt once the baby “died” at the end of the Clone Saga.

Also, the MJ plane crash stuff is from the Byrne/Mackie relaunch …. which was its own awful era unique on to itself. No one defends that.