It is January 2009.

In the climax of Final Crisis #6, Batman points a gun at Darkseid, who releases his Omega Sanction Rays before the Dark Knight can fire his weapon; Darkseid is gunned down. A second later, Batman dies.

The series, published by DC Comics and written by Grant Morrison and drawn by J.G. Jones, didn’t cause a considerable impact in the superhero fandom because it was a known fact that this limited series, despite its repercussions in the entire DC Universe, was but a stage in Morrison’s long arc for Batman. Final Crisis would not only reinforce Dark Knight’s importance in DC’s pantheon of heroes but lift him from the mold that Frank Miller set him decades ago – that was his goal: instead of the brooding down-to-earth crime-fighting stories in the streets of Gotham, Morrison’s Batman was akin to a super-human. His mind operated as a superpower in itself and his stories contained a high dose of supernatural elements in order to elevate the bat-mythos around the character. Thus, their antagonists were reshaped in response – filled with insanity, violence, and sheer villainous malevolence embedded with psychological terror.

In Final Crisis, Batman played a pivotal role in an event that affected the entire universe, surpassing in weight all of his participation in the previous Crisis.

In the story, the Omega Sanction ray described by Darkseid himself is “the death that is life”. For the reader, once the concept was presented, a simple death by those rays wouldn’t mean just a physical obliteration. Batman was hit by them in full force and died, but also sent past in time. Dick Grayson assumes the mantle and becomes the new Batman. Bruce Wayne’s resurrection (or return), also conceived by Morrison, was nothing short of fantastic, as told in the limited series Batman: The Return of Bruce Wayne (published in July 2010).

Fighting Darkseid in a world-scale event was not enough – Bruce Wayne had to fight his way through time itself to go back to his present.

Apropos of death and time…

It is April 2007.

In the immediate epilogue of the Civil War event that torn the Marvel superhero community in the middle, Steve Rogers is shot in front of the NY Federal Court House: the first in the back of the neck, by the villain Crossbones in a distance. The following three in his stomach, by Sharon Carter (Agent 13) who stood right in front of him, brainwashed blind by Doctor Faustus. Captain America dies with his hands cuffed behind his back in Sharon Carter’s arms. Everything orchestrated by the Red Skull. The issue – #25, vol. 5 –, is titled “The Death of The Dream”, written by Ed Brubaker and cinematographically drawn by Steve Epting – the team who brought Bucky Barnes from the dead as the Winter Soldier in the title and made him wield the shield as the new Captain America.

Later on, it was discovered that the gun that Sharon used to shoot Rogers was not a conventional model, but one designed by Doctor Doom. The weapon ‘froze’ Steve Rogers in space and time; he experiences and relives specific and the most important moments of his life and has barely any control of it. He must fight his way back to the present. Those events are told in the limited series Captain America: Reborn, published in July 2009, written by Brubaker and drawn by Bryan Hitch.

A pattern emerges – a hero who is lost in time and must find the way back to his present. Certainly an idea worth exploring in the superhero fictional realm.

It is December 2003.

Thus far, under the guidance of J. Michael Straczynski, The Amazing Spider-Man comic has evolved to new heights – and not as the usual gimmick would state just because a new writer spearheads the title. The proof lies in what has been proposed, applied, and established so far: the possibility of a source to his powers; Aunt May‘s discovery of his secret identity; the beginning of a new career as a science teacher; the return of Mary Jane as his spouse. These are his life’s priorities.

It’s also what makes Peter Parker such an empathetic and charismatic character. Unlike Batman and Captain America, his goals are just the same as for any other man in the adult stage of his real life, who doesn’t live in the superhero comic book fictional universe: it’s the ones he loves the most that counts; it’s what he does with his life, his values, and his job that matters. The mask is just a part of his personality, and not the whole. Peter Parker does desire to lead a normal life; he holds these values important. But because of his powers, he knows what he can do for others: to protect, save, and engage in physical combat, sacrificing his life on the line if necessary, and then prioritize his private life. Bruce Wayne and Steve Rogers’ life philosophies (or creeds) are not it; their lives as caped crusaders and sentinels of liberty are their lives’ purpose. It’s an important distinction.

The title was already in its second volume since January 1999. The last issue of its first volume was #441, published in November 1998; by an editorial counting, if sequentially applied to the second, the half-millenary issue would fall in the 59th. For obvious reasons, so it has been decided, and a three-part story with its climax in the anniversary issue had been conceived to celebrate the existence of a paramount comic book that has revolutionized the industry and pop culture forever.

But this wouldn’t be the first time the company would release a 500th issue milestone: in 1996, Thor became the first Marvel title to reach it (written by William Messner-Loebs, drawn by Mike Deodato, Jr.), followed by Fantastic Four #500 – six years later in September 2003 (written by Mark Waid and drawn by the late great Mike Wieringo). Both comics are very much worth reading.

A landmark issue deserves an essential tale – and on account of Straczynski’s method on absolute character focus, his birthday couldn’t be a more fitting plot to commemorate not only his existence in the popular culture but also in his own (fictional) life. It’s worth reminding the last time Peter celebrated his birthday was on Spider-Man #23 (June 1992) – written and drawn by fan-favorite and Image Comics founder Erik Larsen.

Much had changed eleven years later. The nineties’ superhero formula had to evolve or die – Marvel’s filing for bankruptcy in the end of the century was but one of the symptoms that corroborated the industry’s need to focus on different strategies. With DC’s Vertigo line of comics reaching its creative peak and success during the decade, the teenagers who once flirted with Watchmen and everything else that followed had found fertile territory to explore more sophisticated comic book storytelling, a yearning that their childhood costumed and colored champions could not provide back then; still, some superhero comics disguised this “maturity” with kinetic action, über-sexy characters, visual violence, the occasional bloodshed filled with gore, and harsh dialogue. All the elements were there, but they just weren’t coming together. The readership needed more – the kind that some of the TV series was slowly but firmly establishing themselves by applying serialized comic book formula in their format (ironically enough): an episode was not just an episode – but a part of a bigger “movie”. And more: the characters’ lives were explored and showed depth, regardless of the plot presented.

JMS just so happens to be one of those TV writers (and producers) who utilized the monthly comic book storytelling system into his own science fiction series: Babylon 5. And let us not forget he is also a huge comic book reader for life. When he finally shifted gears to the funny books, using his unique character-approach method, The Amazing Spider-Man title became more than just a funny book in stands: Peter Parker became a man. And now it’s time to celebrate that fact.

Life does happen in cycles, either in fiction or reality.

HAPPY BIRTHDAY – ASM#57-58 (vol.2), #500 (vol.1 – December 2003):

(Covers by Tony Harris and J. Scott Campbell)

After losing a frustrating bureaucratic argument with an evil administrative assistant at school named Julie, Peter talks about it with Mary Jane and Aunt May; he’s angry. Thanks to JMS’s approach to the characterization and proper dialogue, Aunt May has evolved from an oblivious innocent old lady to a woman whose life experience made her the family sage. She asks Peter if Julie had offended him, and explains that, given her uncooperative attitude, she’s only following her nature. Because as a superhero, he has to apply physical violence and that makes him wonder about his, notably now, when the totemic origin of his powers still linger on his mind. An insight worth pondering on.

From their bed, Peter and MJ watch the striking of a red lightning bolt; the unnatural event calls for an investigation, and off goes the friendly neighborhood looking for trouble. Arriving at Times Square, he sees a swarm of Mindless Ones destroying everything in their path – big trouble, but not without resistance: Thor, Iron Man, Cyclops, the Thing, Human Torch, and Mr. Fantastic are in the frontline. This is New York City, home of most of the heroes in the Marvel Universe, so their intervention does not come as a surprise; Spidey himself is just late for the party – the kind that Doctor Strange might be its host. When he arrives, it’s already too late: Reed Richards had made a false move by using a device to open a portal to send the Mindless Ones back from where they came, but doors open from both sides and Dr. Strange announces his nemesis and uninvited guest: Dormammu.

The Sorcerer Supreme engages in mystical combat; the remaining heroes try to at least contain his army of Mindless Ones; while Strange remains in a suspended orb above the ground in fierce combat with Dormammu, some of his minions try to attack him behind his back. Spider-Man sees it and makes the move for the save. But each Mindless One is awfully strong and all it takes is a single sucker punch to send him inside the orb right between the Master of Mystic Arts and the Hellspawn, right in the moment that Strange would cast a decisive spell to cast him away; but Spidey’s accidental presence in the orb alters the spell’s dynamics. Dormammu knows it. Reality fades.

From a void where time and space are nonexistent, Spider-Man recovers himself with the help of Doctor Strange, who explains (also to the reader) that a powerful spell must be cast in order to make them return to their dimension; the space part can be taken care of. Though they’ll be back in their reality, Spider-Man must find his way back through time.

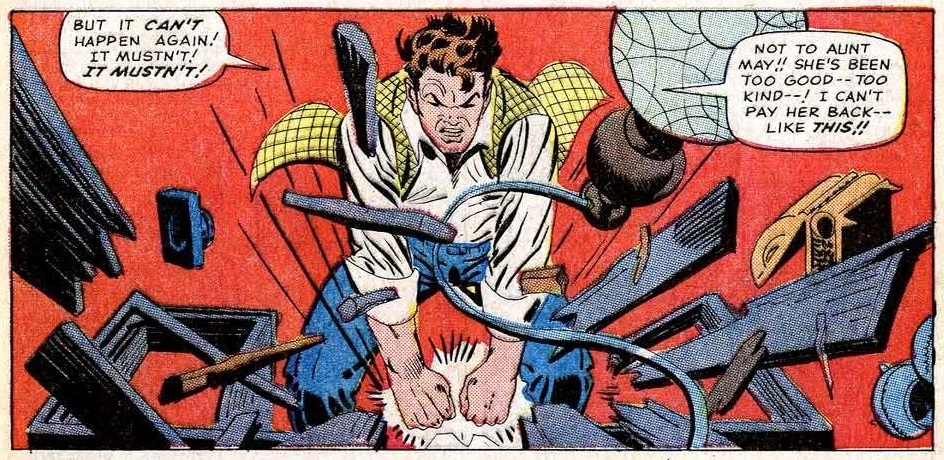

What follows is a tour-de-force that initially puts the hero back to the battleground in Times Square, where the heroes have lost and Mary Jane dies. Then, without warning time shifts; he’s launched into a future – where he sees his future self in a redesigned uniform standing in front of Aunt May’s grave. And older William Lamont is there, aware of his secret identity, surrounded by an armed squad prepared to take him down. The reasons why are unknown. In front of his eyes, time shifts again and he sees his younger self, right in the moment that the spider who forever changed his life is about to bite him. Future and past collide – he’s in a moment between moments, eye-witnessing what it was and what it could come to pass to his own life. His beginning and possible end.

A unique and intimate conundrum that each person in this planet has already fantasized countless times: what if we could actually see ourselves in decisive moments of our lives, in which a single action changed everything – and have the possibility to reverse it? What if we could change our future after seeing it? In the realm of superhero comics, those questions can be answered later. Here, Peter Parker has been given such opportunity; and by realizing what a direct intervention into his past and future means – he chooses not to. An agonizing paradox; he just fought a battle with himself and lost it. Overwhelmed by guilt, Dr. Strange finds him astray in time and sends a spell from a billion years in the future to bring him back to his timeline; he must follow his voice to do so. And along the way, he’ll relive most of his past up to the moment in the present before Dormammu’s arrival. There’s no more future to be seen.

This journey takes Spider-Man to the extreme: time moves forward, leaping throughout some of the clashes he’s been through in his early career, it’s physically demanding and he can barely rest. But he keeps fighting. Straczynski, John Romita Jr., and Scott Hanna use this anniversary issue as a journey to remind the reader why Spider-Man is the best superhero there is due to his life story – the physical and emotional challenges he had to endure – visual homages included:

After reliving such a corporeal trial, the next is nothing short of the crucible: the death of Gwen Stacy. He’s beyond physical and mental exhaustion and wants to give in. Death of beloved ones superseded by madness and violence, and all at once: from his greatest victory to his biggest defeat. It’s just too much, so he keeps still in the darkness. Right then Doctor Strange once more reaches and reminds him of the greatest gift anyone can receive – to make a difference in life. He has made it enough for a hundred lifetimes and still question if it was all worth it. Strange calls to his mind and points out that he’s asking the wrong question. Peter stands and decides to move forward. He knows that the wisdom acquired through the hardest lessons in his life wouldn’t have been gained without all those battles; because that’s how the human spirit works and evolves. That’s what life is: victories. Losses. Choices. Moments in time that make the difference. No fictional character knows this more than Spider-Man. It’s what makes him the best superhero ever created. “Follow my voice. Fight the darkness. Fight despair. Fight until the fighting is impossible.”

Dr. Strange states a metaphor for life.

When Spider-Man finally returns to his timeline, he immediately goes to Mr. Fantastic to tell him that his early action with the device would bring Dormammu to their dimension and destroy everything, despite their best efforts; he asks them to wait for Dr. Strange’s arrival. And so they do; they trust him. Dr. Strange finally arrives and without Dormammu’s presence, he sends the Mindless Ones to their realm through a magical vortex. The day is won. Spider-Man talks to him about it all and The Sorcerer Supreme gives him a small token of appreciation; it’s his birthday. At home, a small surprise party is thrown by Aunt May and Mary Jane; but without extra guests. With the last four pages drawn by legendary John Romita Sr., Peter goes to the roof to open his gift and finds a note inside that he would have five minutes. Technically, Spider-Man saved the world. On his birthday, nonetheless, but without fuzz. Here’s the Universe returning him the favor, by granting him the kind of five minutes that people would pay anything for:

There’s no separation between the Spider-Man mythos and the legendary artist who elevated the character to a popular icon status: John Romita Sr. illustrates the last four pages of the anniversary issue – a meaningful conversation between Peter and Uncle Ben. ‘Nuff said. It’s a moment that will not make any difference for the title’s future continuity, save for the issue alone, and what it represents. No hectic action to push the story forward, neither a villain masterplan to destroy the city and dominate its people nor a deadly secret revealed from a supporting member. Just Spider-Man’s struggle, with Dr. Strange’s help to reach his present time by reliving his own life and fighting through it all over.

That could be very well a metaphor for the birthday meaning: to looking back on life and reminisce on how much time has passed, the growth and evolution through challenges. And also, ASM #500’s intent behind its plot.

A quote from JMS on his writing style:

“For me, writing is about emotion. That’s it. Action, pyrotechnics, stunts, complex plots, sure, all helpful… But even with all that the story will fail unless the audience feels something for the characters. Absent emotion, it’s all just noise.“

Straczynski’s weapons of choice (or themes) applied into some of his stories somehow mirrors Ditko’s distinctive elements established in his most important creations: with Spider-Man, there’s a strong link into the ‘reality’ of being a superhero that often veers into science, given the origins of his enemies and the dangers he faces. With Doctor Strange, obviously, it’s all about magic: the supernatural and mysticism. In this (Spidey) phase, JMS keeps digging deep in uncharted territory crossing both themes, interchanging the scenarios for the characters. Case in point: in issue #500, Spidey is thrown in Strange’s battlefield again. The miniseries Doctor Strange: Beginnings and Endings put Stephen Strange on the other side of the coin: it’s an exploration of his origins when he was nothing more than a pragmatic and selfish surgeon, whose beliefs were heavily grounded in science and the material world. Nothing more.

Under JMS’s mind (and typing fingers), both characters have their origins and thoughts scrutinized by the reader, without dramatic exaggeration.

In the comic book creative corner, some cycles are made of beginnings and ends. Intellectual properties are outliving generations. On that note, it is a fair conclusion that Straczynski celebrates Ditko’s creations in his stories – the anniversary issue here reviewed makes it evident. It’s no news either that Ditko’s work has influenced Alan Moore in his most celebrated work in the comics industry: Watchmen. From characters to themes (our reality is one of them) and style. If Watchmen exists, it’s because of Steve Ditko – the co-creator of Spider-Man.

Straczynski has publicly stated that Moore represents the best in comic book writers and his body of work is of great influence. Thanks to the prolific quality of his superhero stories, JMS ended up being drafted by DC Comics to join a stable of high-caliber writers and artists to conceive an ambitious series: Before Watchmen (2012-2013). Being he one of the writers who collaborated a lot for this series: with Moloch, Night Owl, and Dr. Manhattan; despite the controversy of their existence, Straczynski’s stated his respect for the original series and delivered the same quality of work he did during his tenure at Marvel.

The Dr. Manhattan miniseries written by JMS and drawn by Adam Hughes might be the ultimate example in comics in which a writer approached the same themes using a different story and character; in fact, it answers the aforementioned questions here hypothesized: “what if we could actually see ourselves in decisive moments of our lives, in which a single action changed everything – and have the possibility to reverse it? What if we could change our future after seeing it?” With nearly ten years apart between their publication, the writer delivers the answers.

In ASM #500, Captain America Reborn, and Batman: The Return of Bruce Wayne, the characters were lost in time. As opposed to Dr. Manhattan, whose power goes beyond controlling matter – he has the control of time and space; he can be where and when he wants. It’s a metaphor that can be only applied to the comic book medium. The reader has absolute dominance over the story when holding a comic book: different from a movie, in which we are subject to the platform (movie theater and TV) and follow what is being shown. In a comic, the reader can move forwards and backward in the story; time can stop still, making the pace subjective and absolutely flexible according to the reader’s rhythm, besides being condensed in a format that can be carried anywhere, anytime. Dr. Manhattan represents the metalanguage of the comic book medium.

In Before Watchmen, he is everywhen in his own life, observing the reactions caused by himself – a reversal of what his life could have been, had he not become a superpowerful omniscient being.

Another shared element in both comics is Schrödinger’s cat – a Quantum Mechanics thought experiment which deals with distinct possibilities within a hypothesis. If that sounds like a long stretch for a comic book, let it not be forgotten that just like Jon Osterman (Dr. Manhattan’s identity before his accident), Peter Parker is also a scientist. And JMS had the opportunity to write them both. Most Spider-Man writers have barely explored this trait ingrained in the character; however, he remains the one who pushed it to the longest distance to this day.

“Accidents happen. That’s what everyone says. But in a quantum universe, there are no such things as accidents, only possibilities, and probabilities folded into existence by perception.”

– Dr. Manhattan (as written by J. Michael Straczynski)

Just like Before Watchmen: Dr. Manhattan, The Amazing Spider-Man #500 is the climax of a self-contained three-part story that does not require extended backreading – unlike some of the centennial issues that preceded and succeeded it. It’s a satisfactory reading for anyone who is at least a bit curious about the Arachknight and learn what the’s made of: his origin, his powers, enemies, love life, job, IQ, and more. It respects any reader’s intelligence. It purposely celebrates Steve Ditko’s greatest creations and tales with everything than Stan Lee and John Romita Sr. built afterward.

And more important: the title returns to its first volume original monthly numbering.

The art does not disappoint: John Romita Jr. is at the peak of his game; his double-splash page depicting Spider-Man’s countless battles is an achievement in comic book storytelling. The fact his own father complements it adds more meaning to the title’s well-deserved legacy. Scott Hanna embellishes it all with pitch perfection.

The one flaw is in the color: issue #57 (part 1) marks Dan Kemp’s last work in the title; it’s a shame that he could not stay for the #500th. His luminous style and visual vivacity are gone – especially from the red and blue of Spidey’s uniform – and replaced with a brownish-orange palette, making all the primary colors and luminance fade, thus making each page blend according to the most present color; courtesy of Matt Milla (for this review, all panels had their colors altered in order to emulate Kemp’s palette). The digital calligraphy by Randy Gentile makes the dialogue sincere and direct.

One can only wonder if Straczynski had Watchmen/Dr. Manhattan in mind when conceiving this story. But the plot similarities are undeniable: his Before Watchmen: Dr. Manhattan story is an analysis of how he perceives time. When the character accesses another reality (or timeline) in which he never came to be and grew to be old, the same happens to Spider-Man in “Happy Birthday” – detached from his own timestream. So the question stands: what happens to our sense of belonging and existence and we are not when we are supposed to be? That’s what happened to Peter; but the sole character who can answer that question is Dr. Manhattan.

As for the theme, it can also be analyzed for its meaning: Peter celebrated his birthday on his anniversary issue. A birthday is a memento/remembrance of a cycle – of how old we become and the path we’ve been through to get where we now are. A moment to think about our cycles wherever and whenever we are.

J. Michael Straczynski gives us the ultimate metaphor for birthdays:

“The past tempts us, the present confuses us, and the future frightens us. And our lives slip away, moment by moment, lost in that vast terrible in-between. But there is still time to seize that one last fragile moment.”

It is October 28th, 2020.

Not every Spidey fan gets to celebrate his birthday by celebrating the wall-crawler’s existence through a special anniversary – and his birthday as well. It’s amazing to think that this fictional character grants so much joy to so many people all over the planet. And here we are doing our part so that the fan – you – get to share the same joy we do by every text written, every image posted, every live program, and more.

By the time this review is published, the ASM title reaches its #850th issue and is still going strong; so this post is dedicated to Brad Douglas and all the Crawlspace Staff.

Happy Birthday Peter Parker, and long live The Amazing Spider-Man.

Cheers!

I’m very sorry to hear what happened to you; in no way did I mean to be impatient and I hope I didn’t sound too rude. I was just very surprised and happy to see I still have contents to read. Unfortunately, the “Panel of the day” column sometimes pushes much more interesting articles in the obscurity of second page too quickly (for me, at least).

Even if I haven’t read every Spider-Man issue yet, I totally agree with you on JMS’s run: this is the version I envision when I think about an adult Spider-Man.

Thank you again for your hard work, I wish you all the best.

Thank you so much, Aqu@; through the last months, I had a “The Night Gwen Stacy Died” moment and also moved from a country to another, hence the long pause – typical Parker’s luck.

Still, your comment is much appreciated – thank you so much.

From my side, I aim straight at the style, perspective, idea, meaning, and everything that follows from the creator’s previous and future works; very enjoyable, though the cross-reference and research for every text take a lot of time; writing is not easy.

I enjoy JMS’s run with a passion, and despite its up and downs, it remains to me as one of the most enjoyable Spidey-reads ever made.

Cheers.

Before finding this one out, I thought I read every article; I didn’t realize you were still writing this column. I really hope you’ll continue till the end of the run, because I’m loving it.

Straczysnki’s run has always been one my favourites and acted as my Spider-man comic baptism, so it’s great to relive some of those memories, while learning new reasons to love his run.

I still have to read this particular article, I just wanted to say thank you for your work.

Not that I would have much to add, seeing how deep and spot-on your analysis is.